Berthie viewing book Appalachian Portraits for the first time in 1993 with son Joe and Terry Riddle, a neighbor.

Returned with a local minister known to the family; he read my request, and she reluctantly signed. When the book came out, before seeing Berthie was still convinced it would be no good. As she opened the book and looked through it for the first time, I photographed her and her family. She laughed and studied each picture at length. She loved seeing her husband's pictures and talked about what a good time we all had when we made The Hog Killing. She told me she would keep this book for as long as she lived, together with the other good book she had, the Bible. She keeps personal photos and treasures locked in a trunk at the foot of her bed "so the boy's won't get 'em and go sell 'em, she said.

Published in LensWork Quarterly, Portland, #27, Jan. 2000

“The mountaineer would like to have just one person—one day—come into his hollow and show some sign of approval of the way he has lived over the decades, and the way he wants to live forever. And not try to change him without first knowing him.”

John Fetterman—Stinking Creek

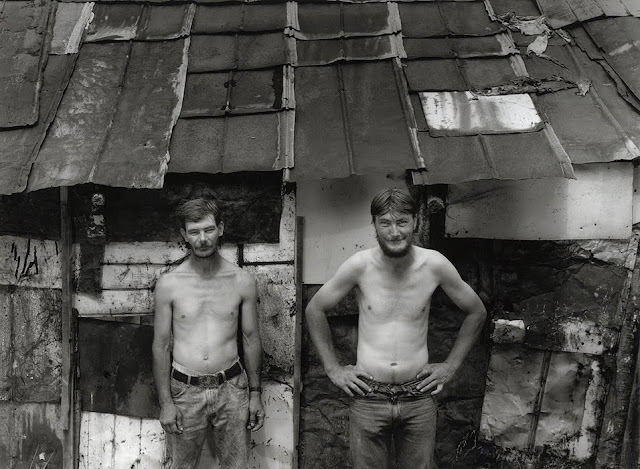

John and Berthie Standing, 1988

Berthie 1988

Berthie lived in a holler called Beehive, a part of Slemp and Leatherwood Ky. I met her through a local preacher who took me to meet her and her family. She told me she had brought into this world16 children. When I first met her, she said she had 8 children living and 8 dead, this was in 1985. Bertie out lived most of her children. I met her husband John and several sons and one daughter. They were open and friendly allowing me to start making pictures with them on the first visit. One-time Berthie ask me to stay for dinner. We had groundhog, potatoes and poke salad.

Berthie told me , when she was hoeing corn one time on a hillside and was carrying a child she suddenly went into labor and just squatted down having the baby in the corn field. Berthie walked home carrying her new baby. As making funeral pictures is a custom of some mountain folk, I had previously photographed two of her children’s funeral’s, Dan who got ran over by a train in 1991 and her daughter Mary who died with cancer in ‘94. In 1998 I photographed Berthie’s funeral in Viper, Kentucky, she was 74 years old when she passed. Bertie lived an extraordinary life.

Other photographs with Berthie and her family can be found in my new book, “From the Heads of the Hollers,” published by GOST Books, London. A high quality 11 x 14 inch portfolio book with vividly detailed images.

Today we are suspicious of "Truth," because we recognize that what is called truth is often only a tool in the hands of those in power [the media], and is often determined by their beliefs and tailored to their requirements.

- - From 2007 interview with local resident.

- "An outsider already has an idea of what they think about me before they meet me or hear me speak. They see your pictures different than I do to. You look at "The Hog Killing, '90," picture, that makes me think, my memories come back, I could feel the cold mornings from my childhood, in the dark and having the water on the fire boilin' before daylight, we killed the hog, the neighbors come over and what a time we had, we was scrappin', workin', it was an event, we made cracklin's, history, that's what it is. These pictures are life. That's fantastic; no one had to tell me that. That meat from your makin' that photo fed those families for three months, we know that, ain't no stagin' to that, that's good as we see it. You don't try and paint no picture that's untrue. There's a life that's goin', but I can still look at 'em and still recall it in your pictures. We have culture, that's what that picture is about and that means everything."

- Hobert White, Eagle's Nest, KY

- _____________________________________________________________

In 2016 I commissioned a video to be made using my photography edited under my direction.

________________________________________________________

The Napier Family

Whilst part of what we perceive comes through our senses from the object before us, another part [and it may be the larger part] always comes out of our own minds.

William James

“The More we neglect those on the periphery of society, the more we invite evil into our lives. The greater our neglect, the greater the chance for evil rebounding upon us.”

Cormac McCarthy

The Child of God

“The portraits that demonstrate the ‘affect’ of lives lived in a state of repression, oppression and trauma mirror through to the viewer identity of his own personal ‘affects,’ something many viewer's may unconsciously deny or not wish to acknowledge within themselves.”

Shelby Lee Adams

|

| Polaroids made at Dan's funeral, 1991 Family photos made at Dan's funeral in 1991. |

Jerry at Brother James Funeral, June '09

Jerry at Brother James Funeral, June '09Examples of 4x5 Polaroids made to share with family before exposing film and for photographer to confirm technical concerns.

James and I have been friends since the mid-1980's.

He is sorely missed by his family and many friends.

James was a man who would give you whatever he had, with a heart of gold. He died mysteriously in the woods in Leatherwood in 2008.

James quote - "I Love This."

Jerry at Brother James Funeral, June '09

Jerry at Brother James Funeral, June '09 Berthie, '88

Berthie, '88 |

| Berthie and the Boy's, 1994 Published in, "From the Heads of the Holler's, 2023, GOST Books, London |

Getting out of the truck, this place felt like being taken back in time. Electric was minimally wired from a black 1/2 inch rubber coated cord that was propped up by wood planks with crooked nails on end. No meter box in sight. The well was hand dug, with a wooden box over it; a hemp rope and metal pulley were attached to draw clear buckets of water. Each house appeared pieced together with wood scraps, cardboard and rusty tin roofing materials. The smoke smelled of fresh pinewood and cedar. This seemingly time warped community was more like visiting an early American pioneer life reenactment village, but it was not.

Meeting John and Berthie Napier was easy, they were friendly, John's laugh was infectious and Berthie smiling, shy, pipe in mouth, head rag on, they were openly glad to have company. When my friend Wayne introduced me as a photographer, John told me about a photographer he remembered, who used to travel by horseback. When John saw my view camera and tripod he nodded, and said, "same thing". Berthie swept the dirt yard with a broom intermittently, shooing the chickens and diddles away, it seemed as a habit of housework. Two of the Napier's sons wandered over from their dwellings and said hello, we shook hands and stood around talking.

When leaving after my first visit, my head was spinning. I had never met a family like the Napiers. Their life was grounded in the pure mountain spirit, I had only witnessed growing up there. The Napiers had somehow survived without adapting to modern ways. That summer, I had a few more visits but always relying on someone taking me in ands out by truck. I was in my mid-thirties then and felt this family was one of the most important I'd met. I went back to Massachusetts and began researching four-wheel drive vehicles and by the summer of '88 I had purchased a new Nissan Pathfinder, if for no other reason than to visit the Napiers.

They had not been photographed by the media or affected by modern ways, and they were open to me. No member of this family owned a TV. If any flaw existed, it was the incongruity in time, with some modern symbols creeping in. The Napier’s appeared to be from a century ago, except for some small details like the logos on men's caps reading "Camel Joe" or "Michael Jackson". When photographing if I asked a family member to remove something I felt was out of character and they resisted, I agreed to their wishes. Keeping the photo sessions as positive experiences is important to opening and reflecting everyone’s natural character. So, some inconsistence's must be tolerated.

Remembering as a child in the late '50's when I was in 2nd grade on through 6th grade, I visited many homes with my mother while she was distributing annually my used school clothes to needy families with other clothing she had collected. Some country homes in the hollers of the '50's had this type of interior wall coverings. We didn't think anything of it, it was a way of keeping the cold wind and weather out. Not everyone could afford insulation or better building materials. I had memories of these kind of environments from the 1950's until I first saw the FSA photographs in 1971. These pictures reminded me of home and I wanted to photographs these environments for myself. Country stores gave away advertising posters, cardboard, and newspapers, we thought of it as shelter. For some this became a tradition. Every spring you redid the walls and ceilings with fresh newspaper and cardboard removing the winters blackened coal dust wall coverings.

Part of the school year, I attended the Hot Spot Elementary School in the holler where my grandparents lived and the rest of the time I traveled with my parents, attending school where ever my fathers work took us, all up and down the Eastern seaboard. Some of my Kentucky classmates wore my older clothes to school. They let me know that they resented it too, which I did not understand at the time. I learned about how the poor were treated from my subjects.

The outside media of the '60's and '70's, during the War on Poverty era, came to Appalachia looking for the same environments. As photographers, journalists and filmmakers the media sent in were outsiders who were not informed about the culture in search of poverty trophies. If the newsprint backgrounds could not be found, [and they often could not] times had changed. Poor families were compromised, paid to paste and glue newsprint to their kitchen walls and homes for photographs and films to be made.

In the summer of '89, I spoke with Berthie about photographing in her living room with the newsprint walls. To my surprise, she spoke proudly of them. Berthie told me, she learned "paperin" from her mother. She talked about the mixture of wheat paste and boiled water used in making the glue, how long it took for it to dry, etc. I made a Sunday 10:30 AM morning appointment with her and John to come and photograph in her living room, with who ever they wanted to be photographed.

Photographing "The Napier's Living Room", 1989 was made to make "amens," as country folk would say. Somehow, to put to rest some personal shame and dissatisfaction with the media within myself and to contribute to this outsider/insider historical litany of images, making this photo was important. It speaks with authenticity for me. It is made with the subject's awareness, cooperation and enthusiasm. That is important to all my portrait and environmental photographs. Further, I had no specific agenda or approach, but many memories and thoughts of how this situation has been rendered in the past.

It is my intent to make photographs like "The Napier's Living Room" with an open mind, listening to my subjects talk about their experiences. To collaborate and make images working together forms relationships and establishes bonding. To photograph and understand this family the Napiers, so proud, with dignity, yet vulnerable. This was the time to photograph, even if the images appear 60 years out of context to modern times. Their lifestyle does not exist anymore and perhaps this culture was documented before with too much insensitivity.

Shelby Lee Adams

May 2007Photo credits: Zwalethu Mthethwa, "Zwalethu Mthethwa", Marco Noire Editore Torino, '99, Italy

Lewis Hine, "America & Lewis Hine", Editor Walter Rosenblum, Aperture,

1977, NYC

Walker Evans, "Walker Evans, Photographs for the Farm Security Administration 1935-1938", De Capro Press, 1973, NYC

All photographs and text copyrighted - © 1978 - 2025 Shelby Lee Adams, legal action will be taken to represent the photographer, the work taken out of context, subjects and integrity of all photographic and written works, including additional photographers published and authors quoted. Permissions - send e mail request with project descriptions.